Malaysian government sources have confirmed to Sarawak Report that the task force seeking the recovery of 1MDB assets seeks to examine the payments made to one of the key former operatives at PetroSaudi International following the jail sentences handed out to two directors of the company in Switzerland last month.

Rich Haythornthwaite, who has recently taken up the role of Chairman of Britain’s major bank NatWest, still partially owned by the UK government, was paid a million ringgit a year (“$500k gross £200k net”) backdated to 2008 according to a contract drawn up in 2010, after the 1MDB joint venture had poured an initial $300 million into the fledgling oil company.

A ‘final contract‘, that matched several versions in the PetroSaudi database, further included two retention payments to be paid in due course totalling $2 million (c RM8 million at the time).

Haythornthwaite worked for the company for eight years thereby potentially earning some 16 million ringgit, although he has subsequently denied that the bonus payments (apparently structured to avoid British tax) were actually made.

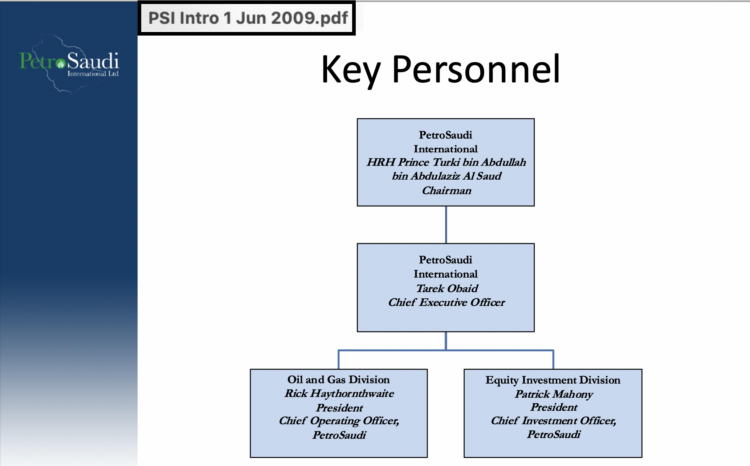

Key Company Player

As Chief Operating Officer, President and the stated Number three in the PetroSaudi International organisation chart, Rick Haythornthwaite played a key part in developing the company’s business.

The parent company was established in 2005 (according to its current website) in Saudi Arabia but had no operating business before PetroSaudi International (UK) was incorporated in 2009.

Mr Haythornthwaite himself stated in an email sent to director Patrick Mahony in 2010 that he saw his role at PetroSaudi International as:

“Leading the development and success of our business operations, ranging from strategy formulation to deep tactical involvement (whatever it takes to move the business forward), including the development of organisational structure, systems and culture; Supporting Patrick Mahony in the new business development and expansion; Using my extensive business networks to source opportunities and facilitate business delivery; Leveraging my City and international reputation should we wish to access the public equity or debt markets; The attraction and recruitment of talent. Helping in every possible way to protect and enhance the PetroSaudi brand.”

Correspondence and documentation also shows that Haythornthwaite was a driving force in the negotiations beginning in June 2009 to acquire a time limited option to enter a so-called Farm-in agreement with the Canadian company Buried Hill, which owned a potentially valuable oil concession in the Caspian Sea gained from Turkmenistan.

The negotiations were financed by a loan from the venture capital company Ashmore, where the now convicted Patrick Mahony was working at the same time as fulfilling the role of Chief Investment Officer at PetroSaudi.

The Caspian Oil Field Fraud

The project was fatally flawed, however, in that it was widely known that the Serdar oil concession belonging to Buried Hill lies in disputed territory. It has yet to be exploited.

A letter of agreement drawn up and sent to PetroSaudi colleagues by Rick Haythornthwaite in 2009 recognised the problem saying

“It is acknowledged by the Parties that the Boundary Dispute could, despite all reasonable endeavours … give rise to circumstances in which the Parties’ ability to conduct Petroleum Operations under or relating to or arising from the Contract is compromised.“

Nonetheless, it was this option that was used by Patrick Mahony to obtain the $2.9 billion valuation of PetroSaudi’s assets that was presented to 1MDB as the basis for the joint venture into which the Malaysian fund invested $1 billion in cash.

The billion dollar cash ‘investment’ was publicly announced in the Malaysian media at the time, and prime minister Najib Razak openly referred to PetroSaudi as having also contributed $1.5 billion – later briefed to newsmen as being in the form of its assets in the Caspian Sea.

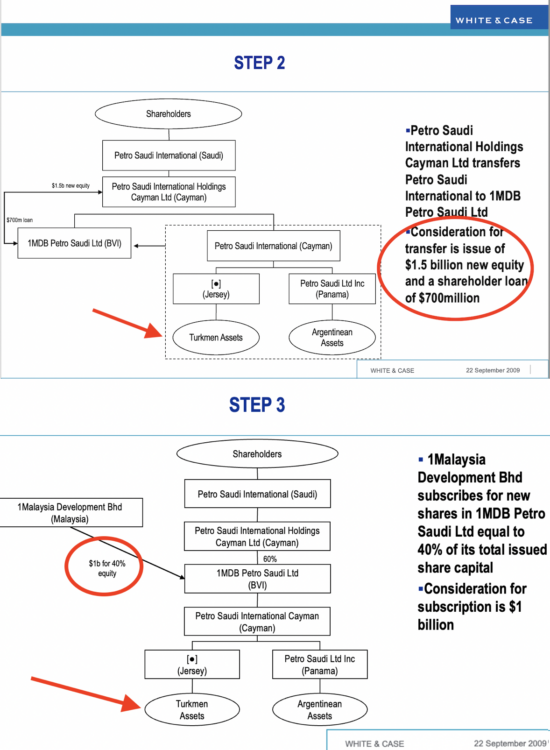

PetroSaudi’s law firm White & Case drew up organisation charts in the week before the announcement of the joint venture deal that featured the Turkmenistan ‘holding company’ as the key $1.5bn asset brought by PetroSaudi into the JV (along with an Argentine venture that soon folded).

Yet PetroSaudi never owned the asset behind that valuation. It merely had an option to buy a 50% share of the Buried Hill venture under terms that would have required PetroSaudi to then fund the hundreds of millions required to begin operations.

Those terms were made clear in the negotiated agreement drawn up by Rick Haythornthwaite which Sarawak Report has sighted.

Rick Haythornthwaite has denied that he had sight of the separate joint venture negotiations with 1MDB or that he was privy to the false claims of ownership being made by PetroSaudi.

Sarawak Report does not contest that denial. However, as the correspondence makes clear, Haythornthwaite was aware the Turkmenistan option was cancelled immediately after the Joint Venture was signed, meaning Malaysia had invested in a company with no active operations.

Indeed, the decision to cancel the contract was communicated to Ashmore by Patrick Mahony and PetroSaudi’s lawyer the day after the 1MDB payment of $300 million to PetroSaudi was banked on 1st October 2009.

Well Run Small British Oil Company?

This week the NatWest Chair’s press relations representative assured Sarawak Report “Rick remains appalled by the criminal actions of directors at the PetroSaudi parent company. He also regrets being initially dismissive of the Sarawak Report’s inquiries….. Misconduct at the parent company level was not visible to Rick or to others at PetroSaudi UK. Indeed, it was actively covered up.”

The statement continued:

“It is important not to mischaracterize the nature and work of PetroSaudi UK, which was a legitimate, well-run small oil company. It had, at various times, exploration and development projects in Turkmenistan, West Africa, Venezuela and Indonesia. It had compulsory compliance reporting and good staff. Rick helped to build this legitimate business, providing an advisory service in good faith.”

Sarawak Report has questioned the rigour of such compliance, which failed to detect the fundamental deceit in the way PetroSaudi International was presented to 1MDB during the joint venture negotiations conducted in London through the lawfirm White & Case.

It was the money defrauded from 1MDB that funded the entirety of PetroSaudi’s future operations, including Rick Haythornthwaite’s backdated contract with PetroSaudi International (UK).

Or Rag Bag Operation?

Despite to the above statement, Rick Haythornthwaite had described PetroSaudi very differently in December 2009, when he called it a rag bag of part timers rather than a well run company with a strong staff.

In an email to Patrick Mahony citing an ‘Organisation Chart’ he’d created to promote PetroSaudi to the Venezuelan government he said it “shows ‘how we are developing’ rather than a rag bag of part timers. Try it on for size.”

In a further email sent to Mahony in 2010, Haythornthwaite referred to his “work with PetroSaudi in uncertain circumstances as an act of good faith …. recognising that the longer term structure still remains uncertain.”

In fact, PetroSaudi had no active operations in Turkmenistan, Africa or Indonesia, and the Venezuela drill ship operation was funded with stolen 1MDB money.

Neither were there full time staff before 1MDB paid hundreds of millions in cash (now frozen) on which no returns were ever made.

This suggests a level of poor compliance and poor due diligence on the part of the senior, if part-time, staff of the British based company and the man who is now in charge of a major public bank.

No Questions Over The Missing $700?

This site has also approached Rick Haythornthwaite over his apparent failure to question the missing $700 million from the original $1 billion that was publicly announced by 1MDB as having been invested in the joint venture, given PetroSaudi itself only received $300 million.

As the above step chart shows, White & Case were instructed just days in advance of the joint venture to execute a fictional $700 million loan from a Cayman Island subsidiary of PetroSaudi to the new 1MDB PetroSaudi (BVI) subsidiary – even before a company bank account had been created to receive it (see the DOJ civil asset seizure suit).

1MDB’s management agreed days later to purchase 40% of 1MDB PetroSaudi (BVI) with the billion dollar payment on the understanding that $700 million of that cash would be used to ‘repay’ the non-existent loan.

When he learnt what had happened the Chairman of the board of 1MDB very publicly resigned. All this was public from July 2015.

The loan device was later spun as having been executed in recognition of the superior value of the assets injected by PetroSaudi into the JV.

However, not only did those assets did not exist but the $700 million did not go back to PetroSaudi but rather to a Seychelles company called Good Star Limited which belonged to Najib Razor’s proxy, Jho Low.

Sarawak Report exposed this theft in February 2015 and by March no less than four Malaysian task forces had been set up to investigate.

Quite apart from the growing chorus from early 2015, PetroSaudi operatives could hardly have failed to notice that since the very inception of the joint venture in 2009 there had been persistent concerns raised in Malaysia about 1MDB’s missing money from this joint venture.

The fund had changed auditors three times amidst inordinate delays in producing audits, the Chairman of 1MDB and board members had resigned, the fund was billions of dollars in debt and its supposed profits had been secreted into a Cayman Islands vehicle named Brazen Sky, that was opaquely concealing its financial situation behind a non-market based self valuation of its own ‘units’.

Yet, 1MDB and the director of PetroSaudi, Tarek Obaid, continued to confirm in 2015 that Good Star Limited was a subsidiary of PetroSaudi, thereby implying that the 2009 loan had been indeed received by the company as part of the valuation negotiations around the joint venture.

When Sarawak Report requested if Mr Haythornthwaite could confirm this claim, instead of doing so he accused this site of “questionable activities” in raising concerns about the venture and said that even if he could help in our enquiries he would not do so.

We therefore question whether his above claims of strong compliance and indeed due diligence amount to the level expected of the head of one of Britain’s most respected banking institutions?

We also question the claim that he was merely working for the British based arm of PetroSaudi International. In fact, all the proposed ventures set up under his management, including the one operational venture in Venezuela using money stolen from 1MDB, were conducted through a web of off-shore companies controlled not by PetroSaudi International (UK) but by the Cayman parent company.

In an email discussing his proposed delayed ‘retention fees’ of $2 million Haythornthwaite again suggested off-shore instruments to hold the money and even appeared to suggest PetroSaudi might choose to send him to work abroad at the time these were due for payment.

This Coutts Bank (a key subsidiary now of NatWest) ‘bond wrapper’ device would give the appearance of being a method of avoiding tax. In a reply to the Guardian Mr Haythornthwaite has said the proposal “would not have been considered appropriate” and denied it was put into practice. He doesn’t remember having suggested it.

Earlier this week Sarawak Report asked the top businessman whether, given these apparent failings and the now proven criminality of the company he played such a key role in presenting as a respectable brand, would he now offer to return those earnings to Malaysia?

After he failed to reply Sarawak Report made enquiries and received a confirmation that the 1MDB asset recovery taskforce is seeking information leading towards a potential suit against Mr Haythornthwaite.

Mr Haythornthwaite has also failed to respond to our question whether he will make a formal apology to Xavier Justo, a former colleague and PetroSaudi director, whom he failed to support after PetroSaudi International colluded in imprisoning him in Bangkok in an attempt to silence his whistleblowing over the 1MDB fraud?

I regard PetroSaudi as my primary commitment

The Financial Times last week reported that Rick Haythornthwaite had explained, when questioned by NatWest, that his connection to PetroSaudi (now erased from his CV) was minimal during the 8 years of his lucrative employment:

“Haythornthwaite told NatWest he worked as a part-time adviser for a UK subsidiary of PetroSaudi for just one to three hours a week between 2008 and 2016, according to people familiar with the discussions.”

This would indeed have rendered his fees to have been astronomical.

However, new documents have since emerged with would appear to confirm otherwise. They include a letter from Mr Haythornthwaite to the now convicted Patrick Mahony, sent in March 2010, in which he gives a very different description of his job and the hours worked in the course of demanding a formal contract from the now wealthy company thanks to the funds from 1MDB:

“At present, I am receiving $500,000 pa gross (ca £200,000 net) for a commitment of two days a week with the potential for a bonus payable over and above this base amount, at the discretion of the ‘the Board’……

I regard PetroSaudi as my primary commitment and have endeavoured to be available whenever the role dictates – as a result, I have spent considerably more that 2 days per week on PSI business and would expect to so do in future….

I have enjoyed and been happy to work with PetroSaudi in uncertain circumstances as an act of good faith and that good faith has been reciprocated. The time has arrived when we both feel that a more appropriate package should be established, recognising that the longer term structure still remains uncertain.

This gives me the opportunity to request a package that reflects my personal objectives and circumstances. My hope is that is works for both of us. Its realisation would, from my perspective, elicit a bond of loyalty, energy and commitment that promises to go well beyond a simple employer-employee relationship…

The proposed components are as follows:

- I will make an average of between 2.5 and 3 days per week available to PetroSaudi, distributed to accommodate the needs of my other roles. This will include a pre-defined 60 days a year when I am available to travel on PetroSaudi business – my 2010 and 2011 diaries have already identified these days. As hitherto, I will always try to accommodate travel request that sit outside theses pre-defined days….”

The letter then goes on to outline the requested terms of the payment contract which was drawn up as described above.